Why Prime Minister’s dismissal of a minister’s ‘hit-and-run’ is deeply problematic

Oli’s casual framing of a criminal offence reflects a deeper culture of impunity and political protection in Nepal

The phenomenon of politics being criminalised and crime being politicised has become a glaring challenge in Nepali society. Political parties and leaders are increasingly disengaged from the struggles of ordinary citizens. Driven by vested interests and willing to stoop to any extent possible, some politicians no longer regard common people as fully human, eroding the very foundation of the legal order.

Philosophically, the terms “criminalisation of politics” and “politicisation of crime” encompass wide-ranging implications, but real-life, emblematic incidents abound. Saturday’s event — a minister’s vehicle hitting a young girl, followed by the dismissive stance of Prime Minister KP Oli and his party — cements how crime gets a political cover.

A vehicle carrying Koshi Province’s Minister for Economic Affairs and Planning, Ram Bahadur Magar — en route to the CPN-UML convention venue in Godavari, Lalitpur — hit a young girl near Harisiddhi Secondary School in Lalitpur-28.

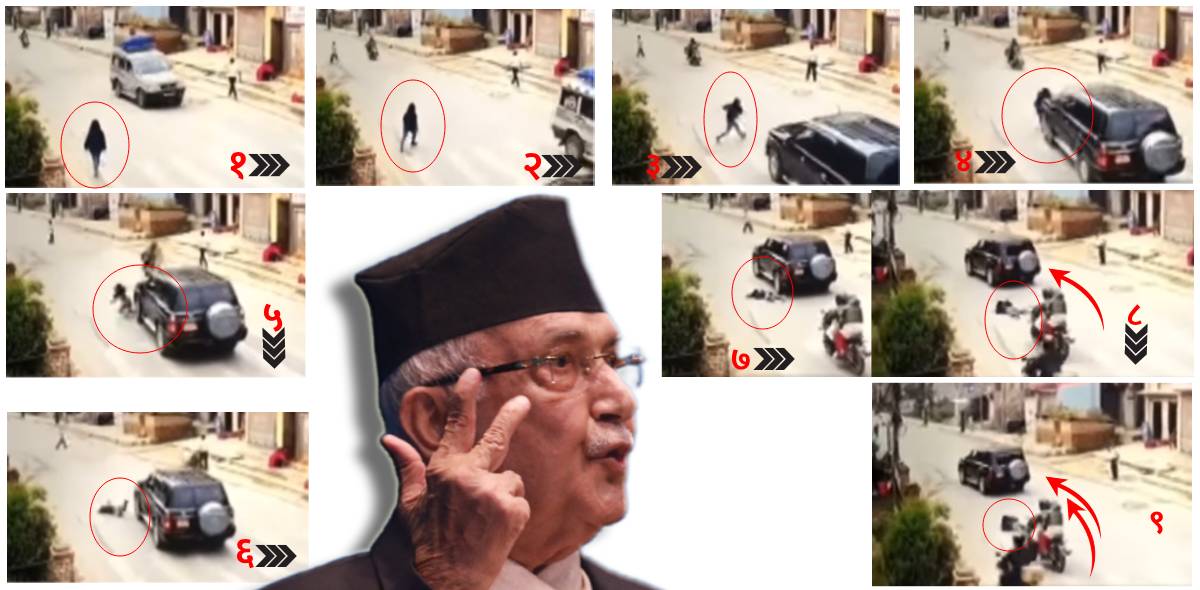

CCTV footage, widely circulated on media and social platforms, shows the girl attempting to pass through a zebra crossing. After failing to notice traffic from her left, she stepped onto the road. Suddenly, Minister Magar’s car approached at speed from the right. Startled, she was struck and fell — but the car didn’t stop. Instead, it sped away. Her foot narrowly escaped being caught under the rear wheel.

Bystanders on motorcycles rushed over, rescued her, and took her to B&B Hospital.

Police confirmed it as a ‘hit-and-run’ — a criminal act where the perpetrator leaves the scene.

Under Section 161(3) of the Vehicle and Transportation Management Act, 1992 (2049 BS), penalties depend on whether intent or negligence is involved. If a victim dies, the offender may face up to one year in prison, a fine of up to Rs 2,000, or both.

These laws apply universally in Nepal — and must. In a democracy ruled by law, no one stands above it — not even ministers or the prime minister.

Yet Prime Minister and UML Chairman Oli chose to normalise this crime, asserting that the accident “just happened” and accusing opponents of using it to politicise and disrupt the convention.

“Basically, a child was brushed by a car and taken to hospital. There was no ill intent. The party will cover her medical bills. I express sorrow. Such unfortunate incidents do occur, but it’s done now, and we had to proceed. That’s why the programme was delayed,” he said.

That the Prime Minister’s chief concern was convention delays — rather than a ministerial car hitting a child — is profoundly troubling.

Known for his offhand jokes, Oli’s flippant remark may endear him to supporters. But he is not merely a party leader — he is the nation’s Prime Minister. His dismissive framing of this incident reveals a terrifying lack of sensitivity.

By labelling it “just an accident”, he not only downplayed a crime — he presumed judicial authority without investigation.

In a country where police and officials often act on political whims — not legal mandates — an incident dismissed by the Prime Minister is unlikely to be pursued. Impunity follows when power shields wrongdoing.

Police reported that the driver later surrendered himself. SSP Shyam Adhikari of Lalitpur confirmed custody. The girl has since returned home after treatment.

“Some money was offered to the family. They did not file any complaint, yet the driver remains in custody,” Adhikari told NepalViews.

But the issue isn’t whether the child or her family is content. The real concern is the Prime Minister trying to normalise negligence — and, by extension, encouraging impunity. Such exceptional events reveal the mindset of those in power and ripple through society.

Just a day before the incident, the Oli government had imposed a ban on 26 social media platforms, including Facebook and X, citing registration non-compliance. These platforms were fully deactivated by Saturday. Advocates for free expression interpreted this move as silencing criticism.

The hit-and-run and the Prime Minister’s callous response sparked fierce criticism among active social media users in Nepal, who circumvented the government ban — an act of defiance in itself against the sweeping shutdown.

A basic principle of democratic society is that the law applies equally. Public office holders have an even greater duty to uphold the law. Yet when those in power trivialise crime rather than reinforcing legal accountability, the foundations of democracy are shaken.

When a speeding vehicle hits someone, the human instinct is to stop. Whether the driver fled under the minister’s instruction or on his own is unclear — but such a vehicle cannot be exonerated by virtue of its passenger. What happened was not merely inhumane; it fell squarely within the legal definition of a crime.

Prime Minister Oli’s attempt to normalise the hit-and-run committed by a minister-chauffeured vehicle raises urgent questions: what kind of political culture are Nepali parties fostering?

The fusion of crime and power begins when minor offences are normalised — as this Saturday’s incident painfully illustrates. This is how impunity and state-protected crime take root, eventually growing into the politicisation of crime or the criminalisation of politics.