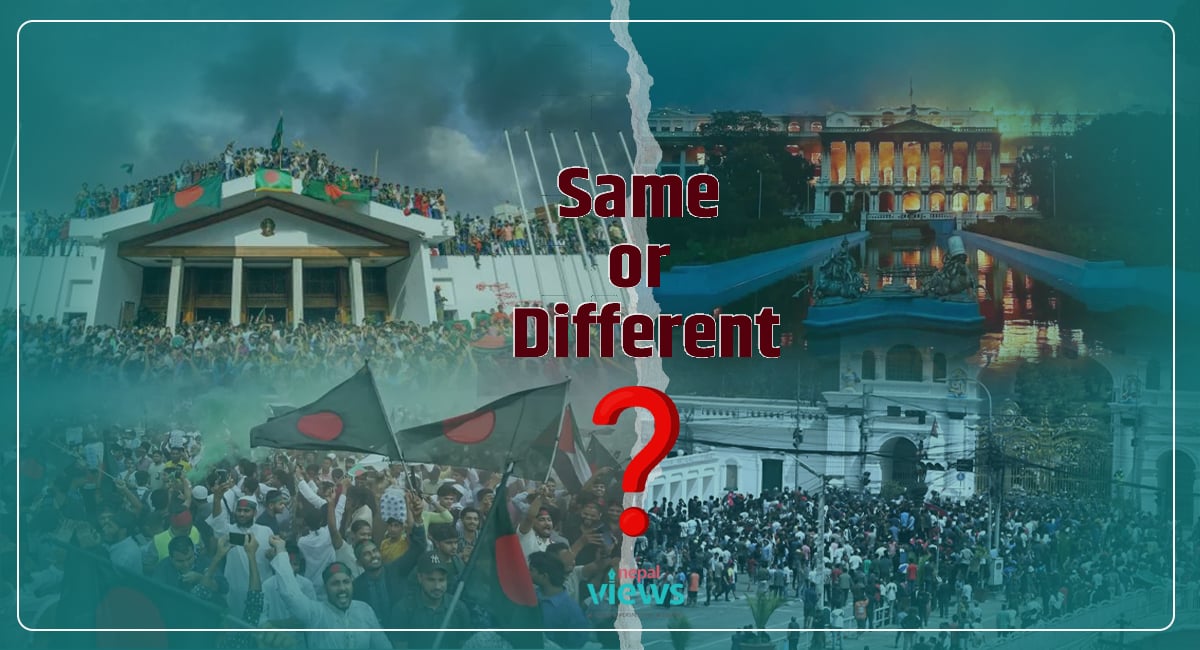

Why classifying Nepal and Bangladesh in one category doesn’t fit

Similar moments of upheaval may look comparable, but the political logics that emerged after power shifted diverged sharply

Kathmandu: Recent analyses have often categorised the uprisings in Bangladesh and Nepal under a unified interpretive framework. Both are characterised as widely supported, youth-led challenges to established political systems, frequently depicted as instances of democratic rectification.

The resemblance seems intuitive at first glance. At an analytical level, it is profoundly deceptive. The issue resides in regarding protest as the definitive political action. Protest constitutes a disruption rather than a resolution. It creates political opportunities but does not dictate the organisation of that area. The quality of political change becomes evident only after agitation diminishes, as new or transitional actors commence exerting authority and defining legitimacy. When the emphasis transitions from protest to post-protest political behaviour, the parallels between Nepal and Bangladesh rapidly diminish.

Nepal and Bangladesh fundamentally vary on this measure.

The youth protests in Nepal arose from discontent with governance efficacy, corruption, and political inertia. As reported by Reuters, the turmoil led to a minimum of seventy fatalities and ultimately resulted in the dissolution of the incumbent government, succeeded by the establishment of a provisional administration responsible for enquiries and electoral arrangements. These developments indicated a substantial fracture.

What is significant, however, is the manner in which legitimacy was subsequently articulated following the rupture. The politics in Nepal following the protest remained rooted in institutional and procedural terminology. Accountability was examined concerning investigations, judicial review, administrative change, and electoral competitiveness. Political disagreement endured, primarily concerning authority, competence, and accountability.

Nepal's enduring societal exclusions persist. Marginalised groups persistently encounter systemic inequities. However, these identities were not utilised as tools for post-protest moral evaluation. Political struggle did not hinge on issues of cultural allegiance or civilisational affiliation. The post-protest landscape, despite its volatility, retained a distinctly civic character.

Bangladesh pursued an alternative path. The protests that preceded the collapse of the former government in 2024 also embodied a democratic impetus. Student mobilisation broadened into a wider resistance against authoritarian consolidation. An investigation by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights suggested that as many as 1,400 individuals may have been killed during the protest period, highlighting the magnitude of the upheaval.

The pivotal transition transpired following the handover of authority. In the immediate aftermath of the protests, numerous credible reports indicated targeted violence against minority communities in various areas. Both Reuters and Human Rights Watch observed that minorities were disproportionately impacted following the political shift. What warrants notice is not just the manifestation of violence but the political context in which it transpired.

Post-protest rhetoric in Bangladesh progressively redefined legitimacy via identity. The deposed dictatorship was discredited not only for its authoritarian methods but also for its perceived secular stance, accommodation of minorities, and pragmatic relations with India. This recontextualization altered the significance of accountability.

Political responsibility became intertwined with cultural and civic affiliation. Once legitimacy is articulated in this manner, minorities are no longer regarded merely as citizens deserving of protection. They serve as symbolic extensions of a discredited political regime. This prompts an additional inquiry that has not been adequately explored in public discourse: if minority communities experienced insecurity in the immediate aftermath of the protests, what implications does this hold for other vulnerable groups, including less prominent religious minorities, ethnic minorities, and politically dissenting individuals without organisational support?

This is where the post-protest political landscape of Bangladesh diverges most significantly from that of Nepal. In Bangladesh, entities purporting to advocate for democratic rectification did not consistently distinguish between institutional reform and ethical reconfiguration. The political shift partially involved redefining valid membership within the political community. Identity served as a heuristic for judgment, rather than institutions acting as the principal arbiters of accountability.

The actions of institutions perpetuated this pattern. Notwithstanding assurances of reform, rights organisations, such as Amnesty International, noted that Bangladesh’s Cyber Security Act preserved the oppressive framework of previous laws, enabling ongoing legal pressure on journalists and dissenters through modified phrasing. Structural transformation trailed after symbolic repositioning.

Electoral advancements further confound the narrative. The forthcoming general election in Bangladesh is set for February 2026; however, the Awami League is prohibited from participating, and a proposed "July Charter" referendum is positioned as a moral evaluation of the past. The efficacy of exclusionary restructuring in fostering accountability or exacerbating polarisation is uncertain; nonetheless, it stands in stark contrast to Nepal's focus on reintegration via competition rather than disqualification through moral delineation.

Even actors originating directly from the protest movement encountered difficulties in maintaining a reformist trajectory. In late 2025, Reuters reported that a student-led party, established following the protests, made a partnership with Jamaat-e-Islami, resulting in internal resignations. This dynamic illustrates a wider trend observed in comparative transition studies: protest organisations lacking institutional discipline are swiftly assimilated into established ideological frameworks.

At this point, the disparity between Nepal and Bangladesh is no longer superficial. The politics of Nepal, following the protests, has continued to focus on governance and institutional rivalry, although poorly. The politics of Bangladesh, following protests, has progressively legitimised identity-based moral reasoning as a standard of validity. The former grapples with efficacy; the latter contends with inclusivity. This is why it is analytically erroneous to characterise both protests as similar movements for "positive change." This contrast prioritises mobilisation over outcomes and intention over political behaviour. It also jeopardises the normalisation of minority insecurity and identity-based exclusion as acceptable consequences of change.

Protests create opportunities for political discourse. They do not dictate the utilisation of that space. Nepal's example suggests that democracies can transform disruption into civic contestation when legitimacy is maintained through procedural means. Bangladesh's example demonstrates how rapidly democratic rhetoric can devolve into moral majoritarianism in the absence of robust institutional safeguards. For "change for good" to maintain analytical significance, it must be assessed post-protest, rather than during the event. Based on that criterion, Nepal and Bangladesh no longer fit inside the same classification.

Harsh Pandey is a PhD Candidate at the School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is also a Life Member at Delhi-based International Centre for Peace Studies.