A new leader, but Congress in a mess ahead of polls

With direct election nominations due on January 20, internal divisions complicate election preparations and prospects for the country’s oldest party.

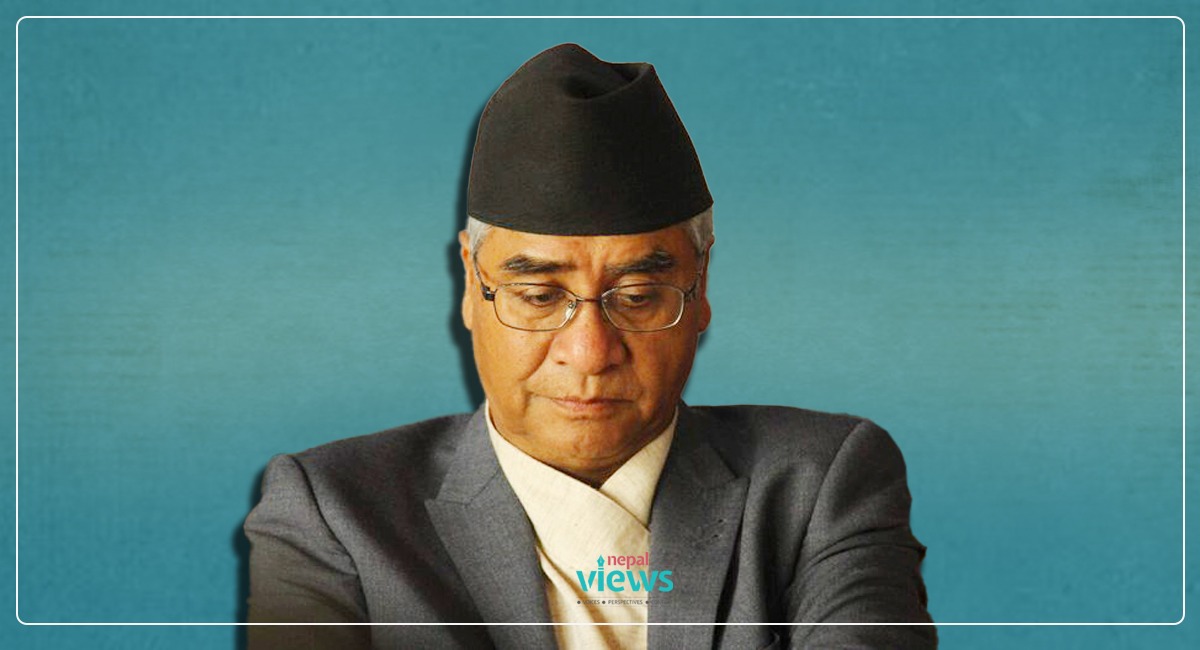

Kathmandu: The Nepali Congress last week witnessed a long-anticipated intervention by second-generation leaders — at least in terms of leadership change. Forty-nine-year-old Gagan Thapa is now the party president, replacing two-time party chief and five-time prime minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, 79.

The transition, however, was anything but smooth. Deuba’s ouster came through a special convention, leaving the party formally under Thapa’s leadership but deeply and vertically divided. The Deuba faction has described the Election Commission’s decision to recognise the Thapa-led Congress as malicious and “a conspiratorial act aimed at derailing the democratic system,” and is considering challenging it in court.

All this is unfolding as the country moves toward parliamentary elections scheduled for March 5. The crisis comes at a particularly inopportune moment. Candidate nominations under the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system are due by January 20 — just days away.

While the “new” Nepali Congress has formed a parliamentary board to select candidates, the task is far from straightforward. With a substantial section of the party — one that emerged as the largest force in the previous elections — now alienated, Thapa and his team must tread carefully. Will they attempt to accommodate leaders from the Deuba faction if they choose to contest the polls? The situation is further complicated by the Shekhar Koirala group, which has opposed the EC’s recognition of the Thapa-led Congress while rejecting Deuba’s plan to go to court.

Ironically, it has also signalled its intention to contest the elections under Thapa’s leadership. How these competing factions will be accommodated remains an open question. Entering an election as a divided house is almost certain to damage Congress’s prospects. Rival parties such as the CPN-UML and the Rastriya Swatantra Party (RSP) are already ahead in the race, having nearly finalised their candidates and begun campaigning.

The UML, the Congress’s traditional rival, retains a strong organisational base. Meanwhile, the RSP — formed just six months before the 2022 elections — surprised many by emerging as the fourth-largest party. With party president Rabi Lamichhane out on bail and Kathmandu Mayor Balendra Shah projected as its prime ministerial face, the RSP has generated significant public buzz. Against this backdrop, the Congress split risks sowing confusion among local, district, and lower-level committees — units that are crucial during elections. The Deuba faction is unlikely to reconcile itself with the current leadership.

Although the Election Commission has left open the option of forming a new party, doing so would prevent it from contesting under a party symbol, as the registration deadline has passed. Independent candidacies would further fragment the Congress vote, offering little comfort to the party as a whole. Under the FPTP system, parties can field up to 165 candidates, while under proportional representation (PR), closed lists of 110 candidates have already been submitted. The Congress’s PR list was filed with Deuba’s signature, while the responsibility of selecting FPTP candidates now rests with Thapa and his team.

Control over ticket distribution was, in fact, one of the key fault lines behind the split — though it was hardly the only one. Calls for generational change had been growing within Congress, particularly after the Gen Z protests. The Thapa group had demanded either a regular or special convention before the March 5 polls. Deuba, elected at the 2021 convention, rejected both demands.

Left with little alternative, the dissidents invoked a statutory provision mandating a special convention if 40 percent of delegates demanded it. By October, over 54 percent had done so — only for the Deuba camp to dismiss the demand outright. The dissident faction proceeded with the special convention. Multiple reconciliation efforts followed, including direct talks led by Thapa and Bishwa Prakash Sharma. Deuba not only refused to step down but also orchestrated the expulsion of both leaders.

It is clear that Deuba, in his final term as party president, was unwilling to be ousted unceremoniously or relinquish control over ticket distribution. He has now lost both. The upheaval has brought about a change in leadership, but it has also left the Nepali Congress in a mess — at precisely the moment when unity matters most.

_LqGDyrjJvx.jpg)